Celebrating Reformation: The Apologetics of Cornelius Van Til

Nearly 500 years ago Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the church door at Wittenberg, sparking the Great Reformation. Of course, in that time we’ve had the opportunity to develop a great many ideas and themes to a degree that was not possible at the start. A key development has been in the area of Christian apologetics. When we consider apologetics before the 1900s the options were pretty slim. Nearly every major apologetic was some form of evidentialism.

Now I need to define that term, because there is much confusion on this point. Evidentialism, as it is used in this post, refers to any apologetic method that seeks to appeal to either philosophical, historical, or scientific evidence (or a combination of these) in support of the Christian worldview. Hence, classical apologetics, evidential apologetics, and cumulative case apologetics would all be varieties of evidentialism.

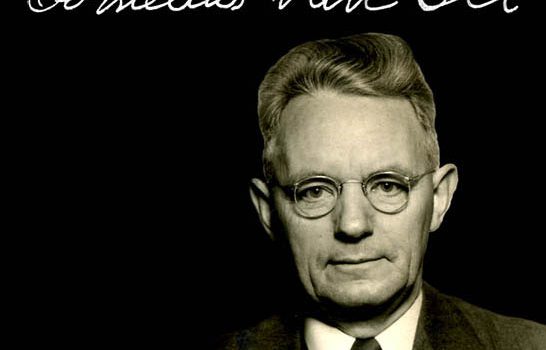

But with the Reformation came Calvin, and with Calvin came a distinct theological system, and with that theological system came implications. Cornelius Van Til, that great professor from Westminster Theological Seminary, was concerned with applying these implications to the defense of the faith. I will follow Ian Clary’s summary in discussing Van Til’s apologetic.

1. Antithesis

One of the defining marks of evidentialist apologetics, as Van Til saw it, was the assumption of neutral common ground between the believer and unbeliever. The evidentialist, regardless of what variety of evidentialism is in play, assumes that the unbeliever can fairly evaluate evidence and thus truthfully recognize its implications.

But, given the doctrine of total depravity, how can this be? Will a soldier favorably and fairly receive a message from his enemy? Of course not! The soldier will read the message with a predisposition to blaming the enemy, to finding fault with the enemy, to making the enemy out as evil as possible. And this is exactly what happens when the unbeliever is given evidence for the existence of God or for the resurrection of Christ. The problem is not necessarily that the evidence is flawed, the problem is the unbeliever, apart from the convicting work of the Holy Spirit, will never respond favorably to the evidence. The unregenerate heart will always view it as a message from the enemy, not to be trusted and believed.

Why is this the case? Because no man is neutral. There is no neutrality, any claim to be “neutral” is a myth. Among opposing worldviews we cannot and dare not promote any myth of “neutrality.” In evangelism, the level of neutrality present is about the amount Hitler would have had entering a negotiating room with Winston Churchill.

The unbeliever, as a rebel against God, has presuppositions that will not allow him to see clearly. The truth is there, right under his nose, but the unbelievers glasses are quite tinted and make everything seem dark. Additionally, the unbeliever is quite convinced he sees everything clearly and so he attempts to act autonomously. That is, he thinks he can set up standards of evidence, rules of inference, and ways of knowing entirely apart from God. He is a creation that stubbornly refuses to recognize his place before the Creator, so his attempted autonomy is rebellion

2. Point of Contact

Given this situation, one might wonder how it is possible to evangelize the unbeliever. If there is no neutral ground where unbeliever and believer can converse, how is evangelism possible?

The Van Tillian answer is that we don’t need neutral ground (which is impossible), we need common ground (which is readily available). Because Christianity is true, the unbeliever lives in God’s world. When the unbeliever uses logic appropriately, he is thinking God’s thoughts after Him, though he doesn’t realize he is doing this. The unbeliever is created in God’s image, but fallen.

Thus, the apologist only has to bring to the forefront what the unbeliever already knows. The apologist confronts the unbeliever at the deepest level, at his presuppositional worldview. Here the task is two-fold, that of polemics and apologetics.

What the apologist must first do is help the unbeliever see how void and useless his worldview really is. This is easy. Because Christ is the One in Whom all things cohere (see Colossians 2), no worldview apart from Christ is itself coherent. The apologist needs to show the unbeliever the inconsistency of his worldview.

For example, I was once talking with a group of atheists about morality. They all seemed to agree that there are no real moral values, at best moral values are relative or evolved to help us survive. I asked them if they had any reason for condemning the Holocaust. About 4 in 5 of them tried to back-pedal furiously. But one of them (a PhD in biology) bit the bullet and admitted there was nothing objectively wrong about the Holocaust, though he added he still had strong personal reasons for condemning it.

That group of atheists had the benefit of seeing a great big hole in their ship. While they did not convert, they did realize they had a bit of a problem. And that is a first step in evangelism.

3. The Question of Authority

Once the unbeliever realizes the problems with his worldview, a true apologetic can begin in earnest. Central to the Christian apologetic is the question of authority. Only God alone can demand our ultimate allegiance.

The unbeliever, who thinks he is avoiding God, has actually just fallen into the trap of idolatry. The unbeliever does worship some god, whether science or mysticism or personal feelings, the unbeliever must yield ultimate allegiance to something or someone.

Because God rightly demands our ultimate allegiance, we give it to Him. And because the Bible is His Word, we yield ourselves to it as well. The answer to all ultimate questions is Scripture alone. The unbeliever’s problem is he has given himself to an authority that is not legitimate. As believers, we speak authoritatively because we yield ourselves to the ultimate authority of God.

Hence, we reason from the Scriptures with the unbeliever, we don’t try to reason to the Scriptures as if they derive their authority from some human discipline. Some might say this is reasoning in a circle, or begging the question. But in truth, everyone reasons in a circle or begs the question in matters of ultimate presuppositions. What evidence can be given for empiricism but empirical evidence? What evidence is given for rationalism but rational evidence?

Because we have already shown the unbeliever that his own worldview is inconsistent, we now assert and demonstrate the supremacy of Christ in His Word. We can revel in the goodness, beauty, and truth of Scripture as the sole foundation for all human knowledge.

4. The Transcendental Argument

This brings us to the last point of the Van Tillian apologetic, and that is the transcendental argument for God. The transcendental argument seeks to demonstrate that the existence of the Triune God is the necessary precondition for all human knowledge. It is powerfully simple, and goes like this:

- If the Triune God does not exist, we cannot know anything at all.

- We do know things.

- Therefore, the Triune God exists.

Human rationality, the laws of logic, moral laws, the existence of beauty, all assume the existence of God. Without the Triune God, there would be nothing to know; indeed, there would be no knowers to know that there was nothing to know. Hence, the Christian worldview is true, and is the only worldview that is coherent with itself and with the world as we see and know it.

Conclusion

While Van Til is controversial, what he did in articulating his presuppositional method of apologetics is call Christians to recognize that Christ as Lord of all is also the Lord of thought. His method has brought Christians to trust in Scripture with supreme confidence, and it has made Sola Scriptura a truth more relevant to daily life. Additionally, Van Til’s apologetic sparked a great movement in Christian counseling, a movement we will consider in more depth in our next post.

Soli Deo Gloria,

Josiah