Holy Week: Palm Sunday

Because today begins the celebration of Christ’s final week, I’m starting a new article series. Throughout this series, I will highlight some of Jesus’ larger actions during his final week, examine them in their cultural and historical context, reexamine where we might be misunderstanding the point of these culminating actions, and attempt to reapply them correctly.

We begin with Palm Sunday.

Jesus was on his way to Jerusalem to die. He left Jericho, walked by Herod’s palace, and took a very lonely, winding, ancient road on his way to Jerusalem. Having told his disciples that the cross lay ahead of him and having spent his whole ministry teaching them that the way to the Kingdom is not through power, but the slow growth of changed lives and loving your enemy and neighbor, while walking that long road Jesus’ disciples are behind him arguing about who will get to be “first” when Jesus overthrows the Romans. After three years, they still don’t get it.

At last, Jerusalem came into sight and Jesus entered first into the the little town to the east called Bethany. There, he raised his friend Lazarus from the dead. The following Sunday, he left Bethany and walked along the Mount of Olives and saw Jerusalem lay in front of him. He walked along the top of the mount to Bethphage. And after walking 90+ miles from the Sea of Galilee, Jesus looks at his disciples and says, “I won’t walk another step. I need a donkey.”

This is significant because Bethphage was basically the city limits of Jerusalem. It essentially served as a signpost that said, “Welcome to Jerusalem.” It’s here that Jesus very intentionally came from the east (Is. 41:2-4; Ez 43:1-5), riding a donkey from the very edge of the city into Jerusalem (Zech. 9:9). Jesus begins his procession into a city that is brimming with people celebrating the Passover. Passover was a significant holiday because it was a reminder of God’s deliverance. It was especially significant at that moment because of the Roman occupation. Knowing this, the Romans regularly sent larger contingents of soldiers to handle the crowds. And Jesus, whose reputation preceded him, came to Jerusalem. From the east. On a donkey.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

After the Jewish people returned from exile in 500 BC, a large group of them vowed, “We will never allow this to happen again. We are going to faithfully obey God’s Torah and Prophets. We will keep His Law as faithfully as we can so that God will never again reject us.” Those who vowed this were called hasidim (the “pious” or “righteous ones”). They desired to serve God alone. No idol worship. No “pagan-ness.” Only serving and obeying God. As time went on, they became known as extremely passionate people. They were passionate about God and their obedience to His Law.

Simultaneously, the geopolitical map is in flux. The Greeks, led by Alexander the Great, have defeated the Persians and Alexander was not only out to expand the Greek Empire, but Greek culture, Hellenism, which promoted Greek language, thought, life, culture, religion, and philosophy. Not long into his conquest of the Middle East, Alexander abruptly died and his rule was passed to his four generals who divided the empire into four separate regions. Judea was ruled for about 125 years by the Ptolemaic Empire from Egypt, however the Seleucid Empire in Syria took Judea by force. Once they were in power, they implemented strict laws prohibiting Jewish worship under penalty of death, forcing the Jews to become Hellenized pagans. They were prohibited from circumcising their sons, reading Torah, blowing the shofar, going to synagogue, sacrificing in the Temple, and were functionally made give up their identity.

The Seleucid Emperor, Antiochus Epiphanies, commanded the worship of Zeus, desecrated the Temple in Jerusalem (some say by slaughtering a pig on the altar), and had nearly all of the Levitical Temple priests murdered. A family of hasidim called the Hasmoneans, better known as the Maccabees, rose up in revolt saying, “We will fight to the death before we will give up our faith.” The hasidim believed that this was the time to act by taking up a knife, a sword, or a spear and, in the name of God, destroying those who would drive them into idolatry. And this group of religious guerrilla fighters succeeded in pushing back the Seleucid Greeks gaining their independence.

Not long after the revolt, the hasidim splintered into two groups. One we know as the Pharisees and the other was called the Zealots. These two sects were both equally passionate about obedience, wanting to make sure every focus of their lives was on doing as God commanded. They were both equally devastated that their forefathers had been exiled from the land because of disobedience. Their only disagreement was on how to respond to disobedience when they encountered it. Even though the authoritarian Hellenistic influence was removed with the revolt, it had taken root and many Jews became Hellenized and functional pagans. The hasidim had a dilemma. They had taken up the sword to defend their obedience and rid themselves of idolatry, but the first time they were fighting and killing Greeks. What should they do when Hellenism began to spring up in their neighborhood, in their family, or in their own home? The Hellenized pagans were now their brothers, sisters, neighbors, and friends. They were fellow Jews. What should they do? This passionate group split into two passionate groups over this issue. Those in the majority, the Pharisees, said, “We will be passionate about obedience and keep Torah and let God fight for us and His Kingdom. We won’t kill our brother. God will deal with them.” But a significant minority, the Zealots, with the same Pharisee theology and passion said, “We will be passionate about obedience and keep Torah and, out of zeal for God, violently oppose Hellenism, idolatry, and paganism at all costs. If anyone gets in the way of God’s rule in this land, we will stop them.” And Jesus came and stood on the stage of history with these people.

After the revolt won the Jews their independence from the Greek Hellenistic pagans, they celebrated the Feast of Booths (Sukkot) because at the actual time of the feast, it was prohibited. There are two things that happen during the Sukkot celebration. First, the Scripture requires the waving of palm branches (Lev. 23:40). Second, we know both from modern and ancient Judaism that the Hallel psalms (113-118) were sung. Sukkot, in general, was an important feast, but this particular celebration became much more significant in the mind of the hasidim, particularly the Zealots. So much so that the waving of palm branches became a symbol for the nationalism and the Zealot movement. It was so closely associated with nationalism that it was put on many Judean coins during their time of independence before the Roman occupation (see the cover photo). To the Romans, it signified revolt. They declared palm branch waving at certain times of the year a crucifiable offense. The Zealots and strong nationalism were also tied to Hallel Psalm 118, particularly verses 25 and 26, “Save us, we pray, O LORD!” (In Hebrew, these first two words are יָשַׁע [ya-sha’] אָנָּא [an-na’]. Anglicized, we put these two words together to create one word for the phrase “Save us.” Hosanna.)

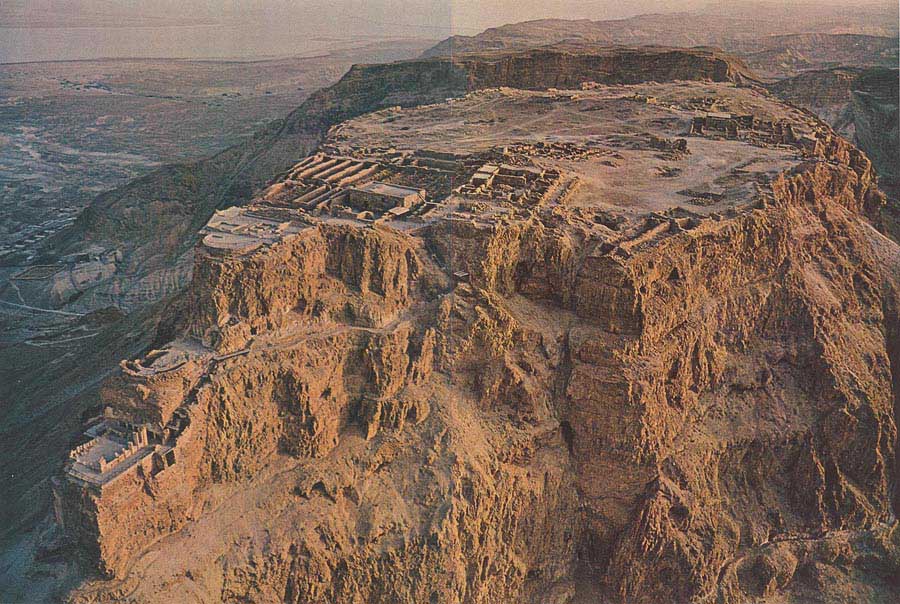

Gamla: Ruins of the secluded mountain fortress city of the Zealots. The synagogue is still intact (foreground), but the homes were all destroyed as they slid down the hill during the Roman siege.

The unofficial capital of the Zealots was Gamla. It was located near the Sea of Galilee, just 5 miles from where Jesus chose to do most of his ministry. There lived 5-8,000 of the most passionately religious, patriotic people the Jews had ever seen. The people of Gamla loved God and built a synagogue around 100 BC (one of the oldest discovered in Judea) which was probably standing during Jesus’ ministry. He may have taught there as he “went throughout Galilee, teaching in their synagogues” (Matt. 4:23). However, the passion of the Zealots came out in violence against anyone, pagan or Jew, who they saw getting in the way of God’s Law. If anyone were to get in God’s way, if anyone forced a Jew to serve someone besides God, if a Jew payed taxes to the Romans who call themselves gods, if anyone took a Jew’s land which had been given to them by God, if a Jew went to Roman theaters or arenas dedicated to their gods, they deserved to die. The Zealots believed they were doing the will of God by killing and violently opposing idolatry. Shortly before Jesus’ ministry began, there was a Zealot who killed a priest for going to the theatre. He was so passionate they called him “Son of the Father” (in Hebrew “Bar-Abbas”). You can understand, then, Pilate’s shock when the high priest chose Barabbas, a murderer of priests, over Jesus.

Jesus chose Galilee for his ministry, using Capernaum as his home base. Though several miles from Gamla, all Galilee was certainly influenced by the Zealot passion for freedom and the anticipation of a warrior-king Messiah. Jesus often needed to correct interpretations of his message as spiritual rather than political (John 18:36; Acts 1:6). On many occasions, Jesus urged those who experienced his power not to report the miracles, possibly to avoid misinterpretations (Matt. 12:16; Mark 1:44). The Zealots expressed great interest in Jesus’ answer to the question about taxes (Mark 12:13-17) and undoubtedly took issue with Jesus’ commands to pray for your enemies, turn the other cheek, and walk the extra mile (Matt. 5:38-48). But the Zealots were almost assuredly the ones who were ready to make Jesus King (John 6:15). The Romans, however, considered Jesus to be part of the Zealot movement (John 18:36) and crucified him alongside two who are not called “thieves” in Greek, but “felons” (Luke 23:33). The felony that was punishable by Roman crucifixion? Insurrection. Revolt. Insurgency. The crimes of a Zealot. Jesus was killed by the Romans for being a zealot, for declaring himself King, and he was hung between two other Zealots as he died. Yet throughout his ministry, Jesus was explicitly clear that his Kingdom was not the Kingdom of the Zealot, the Kingdom of the sword (Matt. 26:51-52).

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Jesus begins his procession into a city that is packed with people celebrating the Passover. Passover was a significant Zealot holiday because it was a reminder of God’s deliverance. And Jesus, who already had a reputation, came to Jerusalem from the east on a donkey. The crowd, then, begins to chant, “Hosanna.” This certainly can mean “Save us from our sin” or “Save us from the penalty of death which we are under,” but in that context on that day in that place, “Hosanna” meant “Save us from these ROMANS!” which, coupled with the palm branches, unequivocally meant, “If you’re the Messiah, if you’re the King, come and destroy our enemies. Wipe out the pagans. Kill them all!”

Painting of Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives. This is the view Jesus would have had as he entered that Palm Sunday.

If you look in your Bible, you’ll see Jesus’ reaction to the palm branches and shouts of “Hosanna” is not a small smile in the corner of his mouth. Instead, he bowed his head and he began to cry. He sobbed uncontrollably with loud noises. He wept and said, “Why have you rejected my offering of peace?” He cried, “If the sword is the message you want, they are going to build a wall around you, throw you and your babies against the stones, and kill you!”

Maybe he wept because he knew what would happen when the Zealot “gospel” won. Maybe Jesus looked ahead and saw Gamla where 5,000+ Zealots died falling off a cliff fleeing from the Romans. Maybe he saw Masada where 1,000+ Zealots died in a mass suicide fleeing from the Romans. Maybe he saw the Temple where 2-3 million Jews died as the Romans destroyed city. All because, like the Zealots, they took up the sword to try to bring the Kingdom of God.

Maybe he wept as he looked out over the city that he had taught over and over and over that the Kingdom comes through serving one another and even his own disciples missed the point.

And he cried.

The Bible records Jesus crying twice. Two city blocks from one another. Within the same week. To an Easterner, this essentially means they happened at the same place at the same time.

The first instance, he was at his friends tomb after telling both of his sisters that he was going to raise him. He had the stone in front of Lazarus’ tomb moved knowing he was going to raise him, but he looked around and saw the pain of the mourners. The compassionate heart of God broke for the hurting and Jesus wept. Then, just two city blocks away, one week later, Jesus sat and listened to people beg for salvation from the Romans with his own disciples caught up in it and he looked out over a city that was about to reject his offering of peace and he broke down and wept with loud wailing cries.

On this Palm Sunday, think of your Weeping Messiah and ask yourself if he weeps with you or for you? Does he ache and cry with you as “those who mourn” (Matt. 5:4) because of your compassionate heart or does he cry for you because you missed his offering of peace by making him into something he isn’t, by twisting his message to fit your own agenda. Does Jesus weep with you or for you?

It’s easy to demonize the Zealots. I don’t know any Christians who would argue for using a gun or a bomb to bring about the Kingdom of God. But don’t be so quick to dismiss them. There is a little Zealot in each of us that says, “We can bring the Kingdom of God if we just had the power. If we just elected the right President or the right Congress, or appointed the right judges, then we would see the Kingdom come.” The Kingdom does not come through political power. That’s the Zealot way.“Well, if we have the right kind of church building or the right ministry programs or the right pastoral staff. Surely, then, we can bring the Kingdom of Heaven.” That’s the Zealot way that says you can bring God’s Kingdom with pressure or force or power or systems. Those are all tools we can wield, to be sure, but the Kingdom comes comes through you and I, the disciples of Jesus, being his hands and feet bringing his healing and peace to a violent world, making new disciples, and teaching them to obey Jesus’ commands.

So this Palm Sunday, remember that there never has been and never will be a savior on any other hill other than Calvary’s. Not Gamla’s hill, not Masada’s, not Jerusalem’s, not Rome’s, and not even Capitol Hill. And the more we look for one there, the more we over look the one on Calvary’s Hill.